And so it begins. Labor Day has come and gone (much to my buddy Gregg’s chagrin!), and the temperatures have begun to cool, if ever so slightly in the “Heart of Dixie.” I tend to work on Substack essays a little at a time, and they can take up to a month to finish. So, as I start working on this piece, there is no “fall foliage” to speak of. Yet, by the time I finish, a patchwork of apricot, maroon, and ochre leaves will cover the ground, and the days will grow short. When I was living well north of here—whether in Chicago, Oxford, or Philadelphia—I greeted this time of year with an admixture of resignation and melancholy. Soon it would be cold and dark, and so it would remain until April. Why fight it? If anything, it’s better to embrace the chill, to cultivate the elusive hygge (“coziness”) treasured in Danish culture: candlelit rooms, coffee under a blanket, whiskey by the fireplace. Alas, by late January, I would realize that hygge can only last so long, that winter pretty much sucks, and I would start pining for spring.

The situation is less volatile in Alabama. The northern half of the state does see four seasons, but genuine cold snaps are infrequent and, even more importantly, short-lived. This is of some comfort. Still, after living out of state for roughly two decades, I can’t help but make hibernal preparations. I’m opposed in principle to raking leaves—aren’t they going to decompose anyway?—but I’m quite adept at visiting our local craft beer distributor and picking up some pumpkin beer, which I’ve learned is actually a Northern delicacy. I’ll also watch The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949) with my daughter, pick up a bundle of firewood, and turn my thoughts to Allhallowtide in general and the Vigil of All Hallows’ Day (or “Hallowe’en”) in particular.

A couple of years ago, I wrote about the relationship between Halloween and the mystery of death, and last year I explored the curious overlap between Halloween and “Reformation Day.” In this piece, however, I want to take a more aesthetic-cultural approach. While I’m not a devotee of horror content, I know my way around the genre. I might go so far as to say that I have a certain fascination with horror—there’s a reason why ghost stories are older the Hebrew Bible—but I have a degree of trepidation as well. This contradiction might be likened to Kierkegaard’s concept of “sympathetic antipathy.” I’m intrigued by horror but also repulsed by it.

I suppose my first ghost story was Charles Dickens’ 1843 novella A Christmas Carol. I have always loved this tale. I would not have put it this way as a youth, but the very notion that there could be ghosts—that there is a supernatural order not removed from, but intimate with, our own natural one—captivated me. Doubtless this is an offshoot of my Christian upbringing. Ghost stories, while not necessarily Christian, often reflect Christianity’s metaphysical and moral picture of the universe. On this view, there is an immaterial realm that touches and even enters into the material one. This interlinkage is not incidental either. The immaterial is the “really real” that precedes and succeeds whatever takes place in the material, at least prior to what Christianity envisions as the final restoration of creation (Acts 3:21). In other words, the immaterial does not oppose the material but haunts it—a word that, taken from the Old French hanter, quite literally means “to be familiar with.” A ghost is not “an undigested bit of beef…[or] a fragment of an underdone potato” (as Ebenezer Scrooge initially quibbles in A Christmas Carol) but a true and, in a certain sense, privileged participant in reality.

In his 1929 essay “Some Remarks on Ghost Stories,” medievalist scholar and author M.R. James (1862-1936) underlines this point. James is known as one of the English language’s most influential horror writers. His anthology Ghost Stories of an Antiquary (1904) is considered a genre classic, featuring tales of occultist madmen (“Lost Hearts”) and demonic relics ("'Oh, Whistle, and I'll Come to You, My Lad'"). Though old-fashioned and staid, James’ tales are notable precisely because of their naturalism. He does not abstract devils and ghosts from the real world but situates them in run-of-the-mill places, from country homes to abbey libraries. As James puts it in “Some Remarks,” proper ghost stories tender “true narratives of remarkable occurrences,” not contrived plots about reason’s ability to “solve” uncanny experiences. The latter, in fact, is neither terrifying nor convincing, since all rational people will grant that some things just can’t be explained.

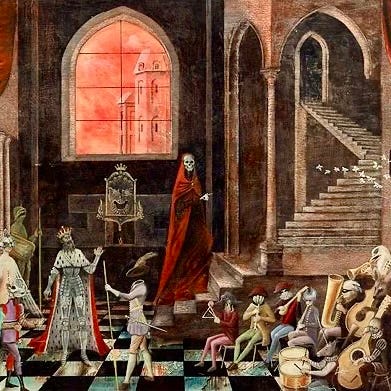

Many of the best and most famous entries in the horror genre instantiate James’ emphasis on the limits of the natural and the reality of the supernatural. Edgar Allan Poe’s famous short story “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842) is a parable about arguably the scariest factum of all—that “death is the end of all men” (Ecclesiastes 7:2). When the clock strikes midnight at a masquerade party for the rich and powerful, each of whom is seeking refuge from a plague known as the “Red Death,” a mysterious figure moves among the throng. Slowly but surely, the partygoers are felled “in the blood-bedewed halls of their revel.” For Poe, death is not merely a “force of nature” but, rather, a malevolent entity opposed to life and, indeed, to the very reign of God: “[The Red Death] had come like a thief in the night…and died each in the despairing posture of his fall. And the life of the ebony clock went out with that of the last of the gay. And the flames of the tripods expired. And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

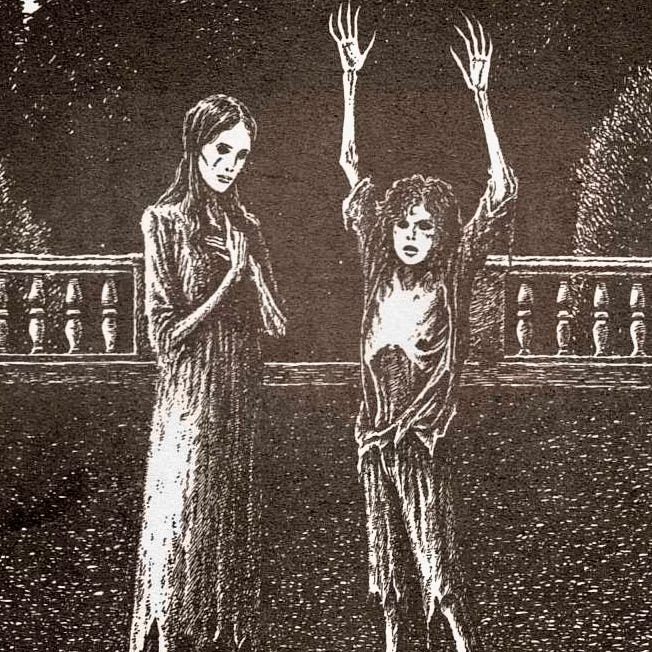

Once dubbed “the most powerful, the most nerve-shattering ghost story” ever written, Henry James’ novella The Turn of the Screw (1898) centers on a haunted estate in Essex, where a dutiful but anxiety-ridden governess seeks to protect her charges from a pair of evil spirits. Although many view James’ tale through a Freudian lens—a reading popularized by the famous American literary critic Edmund Wilson (1895-72)—The Turn of the Screw is ultimately a warning about malefic forces at play in the world. In point of fact, James based the story on a conversation he had with Edward White Benson (1829-96), who served as the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1883 until his death. As James recorded in a journal passage, Benson shook him to the core by relaying tales of “young children…left to the care of servants in an old country-house, through the death, presumably, of parents. The servants, wicked and depraved, corrupt and deprave the children; the children are bad, full of evil, to a sinister degree. The servants die (the story vague about the way of it) and their apparitions, figures, return to haunt the house and children.”

Stephen King’s The Shining is another novel in this tradition. In contrast to the much-celebrated (but ultimately inferior) film adaptation by Stanley Kubrick (1928-99), King’s story takes ghosts quite seriously: they are not products of a deranged imagination but malevolent entities that manifest unconfessed and unredeemed suffering. For King, as opposed to Kubrick, evil is an external supernatural power, which coaxes human participation and, in doing so, perpetuates itself. Death may be the end of all men, but, to quote Bob Dylan, it “is not the end.”

Yet, while Kubrick immanentizes The Shining, a number of the best horror films share the supernatural sensibilities of James, King, and other masters of the genre. In William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973), based on the eponymous novel by William Peter Blatty, a pair of Catholic priests struggle to exorcise a demon who has possessed a young girl. In the scene below, Fr. Damien Karras (Jason Miller, in a poignant role) discovers that the curses and epithets uttered by 12-year-old Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair) belong to no creature of this world.

Similarly, in Tobe Hooper’s Poltergeist (1982), the construction of a planned community on the site of an old cemetery has disastrous consequences. Dismissive of the supernatural, and looking to save a buck, the real-estate developers opt to move the tombstones rather than the dead themselves. Thus they rouse a poltergeist—a German word that combines the verb poltern (“to cause an uproar”) and the noun Geist (“ghost” or “spirit”). This “roaring ghost,” which in the film is given the biblical name of the “Beast” (Θηρίον, variously described in Revelation 12-13), enters the home of the Freeling family through a child’s closet. Yet again, the immaterial is never far from the material; there is even a volatile intimacy between the two.

Even The Blair Witch Project (1999), written and directed by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, holds to this pattern. Famed for its documentary-style technique—the movie is presented as the “found footage” of three missing filmmakers—The Blair Witch Project centers on a local legend. At the beginning of the film, we learn that the woods around Burkittsville, Maryland, a hamlet roughly 60 miles west of Baltimore, are rumored to be haunted by an eighteenth-century woman named Elly Kedward. Accused of practicing witchcraft, Kedward was exiled from the town (known as Blair at the time). She subsequently disappeared and, for centuries, was said to haunt the area, even possessing murderers such as twentieth-century child-killer Rustin Parr. The documentarians hoped to uncover the “real story” behind the legend of the so-called “Blair Witch.” Yet, according to the footage they left behind, the witch turned out to be horrifyingly real.

Still, one might wonder, is there any basis for believing that such tales are, in James’ words, “true narratives of remarkable occurrences”? Are we still capable of being terrified by the supernatural? Before addressing these questions, it’s important to consider the history of ghost stories. According to the English philologist and Assyriologist Irving Finkel (1951-), the word for ghost first appeared on a cuneiform tablet roughly five thousand years ago. This term, in all likelihood, stemmed from burial practices during the Upper Paleolithic period, when the dead began to be interred with various “grave goods,” including jewelry, tools, and weapons. This ancient practice carried with it three assumptions:

That something of the human being survives death.

That this “something” is capable of going to a place beyond the grave.

That this “something” also capable of returning to the earth.

These beliefs, Finkel adds, are precisely what distinguishes humanity from “the whole animal kingdom.” Whereas other animals have no “inkling of their inner self finishing up somewhere once the proud body [has] collapsed into chemicals,” human beings have developed cultural, philosophical, and theological systems that “strive against the prospect of the final annihilation of self.” Ghosts are an “inexpungible” aspect of this striving. Indeed, Finkel goes on, ghosts were once “part of daily life,” so much so that they were taken “utterly for granted.”

It is hardly surprising, then, that ghosts are featured in the most ancient stories of world literature. In Book XI of Homer’s The Odyssey (ca. 8th Century BCE), Odysseus conducts a nekyia—a rite by which the ghosts of the dead are summoned and questioned about the future. Aeschylus would later use a similar conceit in his dramatic trilogy the Orestia (5th Century BCE). Similarly, the collection of Middle Eastern folktales known as One Thousand and One Nights (أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ) features stories about jinn, demons, and ghouls. Such ghostly traditions have persisted over the centuries, cropping up in the works of Shakespeare (Julius Caesar, Hamlet, Macbeth, etc.), Samuel Taylor Coleridge (The Rime of the Ancient Mariner), E.T.A. Hoffman (who is most famous, at least today, for his supernatural Christmas novella The Nutcracker and the Mouse King), and Sir Walter Scott (Redgauntlet). Indeed, it was in the wake of Scott—roughly the mid-nineteenth century—that ghost stories emerged as a distinct artistic genre, detached from popular myths, folk legends, and scriptural parables. In this regard, Poe, M.R. James, and Henry James are clearly major figures, but there are many others besides, including Washington Irving, Edith Wharton, Shirley Jackson, and Stephen King. To a greater or lesser degree, each of these authors can be seen as inheriting and expanding the ancient tradition of ghost stories. Of course, films that tread the same ground could also be added to this list.

In fact, Hallowe’en has its own roots in the supernatural, highlighting what might be called (with a nod to David Bentley Hart) the “terror of the infinite.” Allhallowtide is a three-day liturgical season, which focuses on the reality of death and the afterlife. It takes the common assumption “that something of the human being survives death,” situates it in the context of Christian teaching and worship, and clarifies its meaning for those who practice the faith. The “pivot point” in this “Triduum of Death” is All Saints’ Day (or All Hallows’ Day), which, although originally celebrated in May, was moved to November 1 in the eighth century, when the anti-iconoclastic Pope Gregory III (731-741) consecrated a new oratory in Saint Peter’s Basilica to Christian martyrs and saints. On All Hallows’ Day, the church honors the souls of the dead in heaven—the “Church Triumphant” (Ecclesia triumphans)—and centers its practice on recollecting saints and martyrs, whether known or unknown. These are the ones who enjoy “perfect life with the Most Holy Trinity…[a] communion of life and love with the Trinity, with the Virgin Mary, the angels and all the blessed” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, ¶ 1024).

The Feast of All Hallows is bookended by two lesser, but hardly unimportant, holy days. The third day of Allhallowtide, which falls on November 2nd, is known as All Souls’ Day. It has been set aside to commemorate baptized Christians who have died and yet remain in purgatory—in other words, those who belong to the “Church Penitent” (Ecclesia poenitens). Of course, “purgatory” is a contentious subject in the history of Christian theology, though, with regard to the present discussion, it is notable that its roots lie in Jesus’ parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19-31). This is arguably Christianity’s first “ghost story,” and it suggests that the human person, along with her remembrance of earthly life, survives after death—and not necessarily in a felicitous way. In the story, after all, the rich man suffers the “torments” of hell, while the poverty-stricken Lazarus receives consolation in the so-called “Bosom of Abraham.”

Yet, if those in the “intermediate state” of purgatory are being cleansed as they prepare to join the Ecclesia triumphans, how do those who have refused both holiness and even penance fit into Allhallowtide? According to tradition, it is these souls who are remembered on the Vigil of All Hallows, also known as Hallowe’en. Of course, such persons are not recalled as exemplars but, rather, as “cautionary tales,” whose “damnation” is to be avoided at all costs. Indeed, the word “damn” itself stems from the Latin noun damnum, which can be translated as “damage” or “loss.” And what have “the damned” of Hallowe’en lost? Ultimately, and essentially, their punishment is not “fire and brimstone” but exclusion from the Beatific Vision or “the contemplation of God in his heavenly glory” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, ¶ 1028). This eternal separation from the Beatific Vision constitutes the “pain of loss” (poena damni) that inheres in mortal sin and its rejection of God as one’s origin and end: “And…the bridegroom came; and they that were ready went in with him to the marriage: and the door was shut. Afterward came also the other virgins, saying, Lord, Lord, open to us. But he answered and said, Verily I say unto you, I know you not” (Matthew 25:10-12).

Thus Hallowe’en is indeed a day of terror—not of psychotic murderers, not of aliens or UFOs, not of wild animals, but of the infinite loss of God. The proper object of “fright night” is not natural but supernatural, not immanent but transcendent. As has been seen, many of the great stories in the horror genre understand and draw on this insight, shifting our consciousness to the inevitability of death (“In Adam all die” — 1 Corinthians 15:22), the reality of the afterlife, and the terror of malevolent forces that would keep us from a “happy death”: “Death would have no great terrors for you,” Thomas à Kempis writes in The Imitation of Christ (De Imitatione Christi, ca. 1418-27), “if you had a quiet conscience…. Then why not keep clear of sin instead of running away from death?”

In recent years, however, the theology of Hallowe’en has taken a backseat to more mundane, secular concerns. Whereas previously the Vigil of All Hallows was but one part of a triduum—and, in truth, the “minor” day of the three—today Hallowe’en is one of America’s most popular holidays. Indeed, it is also rapidly growing in importance. Hallowe’en has, in short, become a holiday unto itself, detached from its wider supernatural meaning and thereby rooted in death as such. This shift can be seen in the evolution of the horror genre as well. To give a mere snapshot of this phenomenon: when Terrifier was released in 2016, it was a low-budget indie slasher film centering on a mute serial killer known only as “Art the Clown.”

Since then, it has developed into a full-blown multimedia franchise, consisting of six feature films (including Terrifier‘s anthology film “relatives” in the All Hallows’ Eve movie series), comic books, video games, and sundry merchandise. While Terrifier auteur Damien Leone has stated that the franchise draws on “a lot of biblical imagery and metaphors,” its calling card is graphic violence, so much so that viewers have reported vomiting and passing out while watching the Terrifier films. Needless to say, such “word of mouth” was embraced by creators and fans alike. As Leone tweeted in October 2022, “To everyone saying that reports of people fainting and puking during screenings of Terrifier 2 is a marketing ploy, I swear on the success of the film it is NOT. These reports are 100% legit. I wish we were smart enough to think of that…But then again we didn’t need to.”

Of course, slasher and splatter films are nothing new, and more than one has been turned into a lucrative horror franchise. Nevertheless, as film critic David Edelstein famously put it, the horror genre is slowly but surely evolving into “torture porn”: “As a horror maven who long ago made peace…with the genre’s inherent sadism, I’m baffled by how far this new stuff goes—and by why America seems so nuts these days about torture.” Edelstein’s observation is salient, but he need not be baffled by this development. When horror stories no longer center on “true narratives of remarkable occurrences,” they exchange the terror of the infinite for the terror of the finite. In this newer and darker version of Hallowe’en, the spectacle of psycho-physical pain, suffering, and death becomes an end in itself, not an ethico-spiritual lesson pointing one towards eternal life. Far from delivering human beings from anxiety and fear, the detachment of horror stories from theology turns out to be something scarier than the possibility of hell—the reality of a “culture of death” bereft of both existential meaning and transcendent hope.

Horror has definitely taken a turn in this generation. Feels like the overall shortened attention span of the 2020’s keeps movies reliant on shock factor—as evidenced in movies like Terrifier. With that said, there is a section of horror still committed to the narrative, even if it’s harder to find.

“Death confronts humanity with an incomprehensible, inexplicable, and unassailable reality.”

As Christians, we can stare into that gaping yawn of infinity, not with terror, but with hope. I assume a “culture of death” derives from the absence of hope. I think of Auden’s, “we who must die, demand a miracle…”

This was an excellent essay.