Last Advent, I wrote a substantial essay about Søren Kierkegaard’s assessment of Christmastide and its relation to Christian life and thought (see the link below).

Famously, Kierkegaard has been labeled “the Melancholy Dane,” and he spent the last several years of his life censuring the Danish state church’s acquiescence to secular society. Predictably, then, Kierkegaard’s views on the Christmas season are incredulous. Yet, as he ultimately makes clear, the problem is not the celebration of the Christ Child as such; it is the elimination of paradox—and thus the possibility of offense—from yuletide joy. If Christmas is to retain to its true significance, says Kierkegaard, then it must be confronted as an irreducible divine mystery, incapable of being translated into bourgeois consumerism and/or socio-political agendas. In the Nativity of Jesus we are not confronted with God’s flabby deference to human sinfulness but, rather, His tangible passion to overcome it.

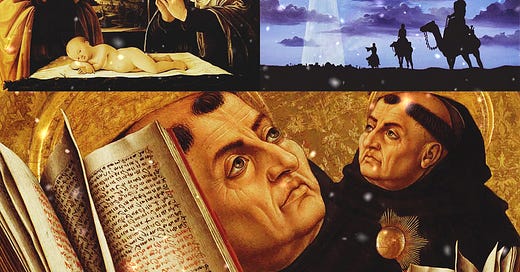

There is much to recommend in Kierkegaard’s analysis of Christmastime in the modern West, although the inner logic and meaning of the season do not receive his sustained attention. Enter St. Thomas Aquinas (ca. 1222-74 CE), the “Universal Doctor” (Doctor Communis), so called because his writings encompass the entirety of Catholic teaching. Ever the systematician, Thomas slowly but surely works his way to “Christ’s Nativity” (De nativitate Christi) in the Third Part (Tertia Pars) of the Summa Theologiae—a massive, trinary project that Thomas started writing in Rome around 1265 yet fell short of finishing before his death on March 7, 1274. It has been frequently observed that the Summa is structured in accordance with its overarching theme: all things come from the eternal God (exitus), and all must return to the eternal God (reditus). Across the first 59 questions of the Tertia Pars, which are collectively entitled “The Incarnation” (De Incarnatione), Thomas attends to the essential role that Jesus Christ plays in this reditus. With this in mind, it is notable that the prologue to this series of questions immediately makes reference to the Gospel story of Christmas: “Our Savior the Lord Jesus Christ, in order to save His people from their sins (Matt 1:21), as the angel announced, showed unto us in His own Person the way of truth, whereby we may attain to the bliss of eternal life by rising again” (ST III, Q 1, A 1, pr).

For Thomas, then, Christmas has to be understood in relation to “incarnation.” The word itself is a noun of action, derived from the Latin verb incarnari (“to be made flesh”). Yet, as a theological concept, it is more than a little perplexing. Thomas admits this problem right at the outset of the Tertia Pars. The first question he explores is “The Fitness of the Incarnation” (De convenientia incarnationis), starting with the issue of whether or not it is appropriate for an eternal Spirit to be united with mortal flesh. One might protest, after all, that just as it would not be fitting “to paint a figure in which the neck of a horse was joined to the head of a man,” so is it not fitting to unite the divine and the human, since “God and flesh are infinitely apart” (ST III, Q 1, A 1, ob 2). But Thomas says that this is an accidental, rather than an essential, problem. For what is God but goodness itself? Drawing on the writings of the Neoplatonic philosopher and early Christian mystic known as Dionysius the Areopagite, Thomas explains that the incarnation of the Son of God is suitable when one considers precisely what goodness is:

To each thing, that is befitting which belongs to it by reason of its very nature; thus, to reason befits man, since this belongs to him because he is of a rational nature. But the very nature of God is goodness, as is clear from Dionysius (Div. Nom. i). Hence, what belongs to the essence of goodness befits God. But it belongs to the essence of goodness to communicate itself to others, as is plain from Dionysius (Div. Nom. iv). Hence it belongs to the essence of the highest good to communicate itself in the highest manner to the creature, and this is brought about chiefly by His so joining created nature to Himself (ST III, Q 1, A 1).

And yet, one might still protest, why should God’s union with a “created nature” be with “the frail body of a babe in swathing bands” (ST III, Q 1, A 1, ob 4)? Wouldn’t a hulking warrior or a person of prodigious intellect be more appropriate? Yet, says Thomas, this objection confuses “corporeal things” with the nature of God, whose power is such that He does not need to change in order to accommodate a created entity. Incarnation does not reduce God to that which he unites himself with, since “God is great not in mass, but in might” (ST III, Q 1, A 1, ad 4).

This opening article of the Tertia Pars provides the foundation for Thomas’ later treatment of “Christ’s Nativity” and, by extension, its celebration during the liturgical season of Christmastide. The topic is, of course, rooted in a pair of New Testament accounts:

Matthew 1:18-2:23

Luke 2:1-20

Both of these Gospels were completed by around 100 CE, and, according to Adam C. English, the ritual observance of Christmas began soon afterwards. Yes, there was debate in the early church about the precise date of the Savior’s birth, but the jubilee itself “sprang up organically from the authentic devotion of ordinary believers.” By the fourth century, many of the formal aspects of the Christmas feast were settled. It was around this time that Pope Julius I (280-352 CE) allegedly decreed that Christmas would be celebrated on December 25, and it was also around this time that the earliest artistic depictions of Christ’s Nativity began to appear—for example, the “Nativity scene” that adorns the so-called “Sarcophagus of Stilicho,” which is carved out of marble and today used as the base of the pulpit in Milan’s Basilica of Sant'Ambrogio.

As is well known, the Matthean and Lukan chronicles of Christ’s birth differ in a number of ways. However, both emphasize that Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit (Matthew 1:18, Luke 1:35) and born of “his mother Mary” (Matthew 1:18, Luke 1:26-28). Both likewise agree that, when it was time for Jesus’ birth, the event took place at an actual historical locale—the town of Bethlehem (בֵּית לֶחֶם) in the Herodian kingdom of Judea (Matthew 2:1, Luke 2:1-16), today located in the Palestinian territory known as the West Bank (الضفة الغربية). Finally, Matthew and Luke also record that Joseph (the legal father of Jesus), Mary, and Jesus eventually settled in Nazareth (נָצְרַת), a small city in the southern part of Galilee, roughly 90 miles north of Jerusalem in northern Israel (Matthew 2:22-23, Luke 2:39-40). It is clear, then, that the two birth narratives are very much rooted in the real world; they are not woolly mythologies but incarnate accounts.

This is the basis for Thomas’ analysis of “Christ’s Nativity” in Question 35 of the Tertia Pars, and it explains why his philosophy of Christmas is so preoccupied with the rugged, “flesh and blood” business of bodily life. The first several articles of this Quaestio attend to the birth of Christ as such. When it is said that the holy day celebrates Christ’s “nativity,” a word that comes from the Latin adjective nativus (“produced by birth”), who exactly was born? Was it God Himself, a “normal” person, or some “third thing” whose essence came into being? In effect, Thomas answers “none of the above,” arguing that “in Christ there is a twofold nature: one which He received of the Father from eternity, the other which He received from His Mother in time” (ST III, Q 35, A 2). In this way, Thomas is quite clearly adhering to the dogma of the Hypostatic Union, which states that Christ is a single “person” (or ὑπόστασις, typically transliterated as “hypostasis”), who subsists in two natures, divine and human. Thus Christ has been born twice—eternally of God the Father but also temporally “in these latter times for our sake” (ST III, Q 35, A 2).

Of course, it is this second nativity that we celebrate at Christmas, and it is also the reason why Christ’s mother Mary plays such a central role in the banishment of humanity’s “sinful night and endless doom.” The notion that the Son of God has entered into time and become a human being is paramount to the season, but it is only possible in and through a temporal, fleshly vessel—namely, the mother of Christ. In Articles 3-6, Thomas turns to Mary herself, and this amount of attention may seem surprising, given that it constitutes half of Quaestio 35. Not all of this material is unexpected, however. Articles 3 and 4 effectively repeat the doctrinal formulations of the well-known ecumenical council held in the ancient city of Chalcedon (part of present-day Istanbul) during the autumn of 451 CE. On the other hand, Articles 5 and 6 are more curious. They endeavor to think through the thorny logic of declaring that “the Blessed Virgin is the Mother of God” (ST III, Q 35, A 4).

Article 6 is especially eye-opening. Citing a line from a sermon given by St. Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE), Thomas reasons that Christ’s birth was entirely painless, both for mother and son. This is not because Mary and Jesus were incapable of feeling pain altogether; it is because the (temporal) birth of the Savior is sui generis. Since Christ was conceived by the Holy Spirit, and thus outside of normal sexual intercourse, his birth was not afflicted by the so-called “Fall of Man.” Yes, God told Eve, “‘I will make your pains in childbearing very severe; with painful labor you will give birth to children’” (Genesis 3:16), but this is an extension of Adam and Eve’s culpable loss of innocence and the ensuing burdens of sexuality (Genesis 3:16-19). These consequences, however, do not apply to “the Virgin-Mother of God,” who herself was conceived without original sin (to be sure, Thomas here implies dogma of Immaculate Conception, centuries before its promulgation in 1854) and who bore Christ “without the defilement of sin” (ST III, Q 35, A 6, ad 1). Whatever corporeal and earthly suffering may one day befall Jesus—and indeed it will—this misery, Thomas asserts, will be chosen by Jesus “in order to atone for us, not as a necessary result of that sentence, for He was not a debtor unto death” (ST III, Q 35, A 6, ad 1).

And yet, insofar as Christmas is about the Incarnation, it also dovetails with the experience of being “thrown” (to use Martin Heidegger’s expressive wording) into space and time. It is not enough to merely assume a human body; that body must enter into history too. For history, even though it is marked by contingency and sin, remains the very theater of God’s salvation—what the Lutheran theologian Johann Tobias Beck (1804-78) famously termed Heilsgeschichte. With this in mind, the final two articles of Quaestio 35 turn to where and when Christ was born. These things matter precisely because they are unavoidable features of incarnate life: we all have to be from somewhere, and we all have to belong to a certain historical era.

In Article 7, Thomas begins by arguing that Christ’s birthplace in Bethlehem is appropriate, even though it is a relatively small city. Given Christ’s command to “preach the gospel to every creature” (Mark 16:15), Thomas wonders if it “would [not] have been easier if He had been born in the city of Rome, which at that time ruled the world” (ST III, Q 35, A 7, ob 3). And yet, Bethlehem made sense for two main reasons. First, and most famously, it underlined Christ’s connection to David (דָּוִד), the third monarch of the United Kingdom of Israel, who himself was born in Bethlehem. At the same time, however, the relative insignificance of Bethlehem underscores the paradoxicalness of the Savior—that he is not recognizable by his strength but by his humility, that God’s kingdom does not correspond to a finite political power but to the total transfiguration of the world. As Thomas puts it, citing the Council of Ephesus (431 CE):

If He had chosen the great city of Rome, the change in the world would be ascribed to the influence of her citizens. If He had been the son of the Emperor, His benefits would have been attributed to the latter’s power. But that we might acknowledge the work of God in the transformation of the whole earth, He chose a poor mother and a birthplace poorer still (ST III, Q 35, A 7, ad 3).

Yet, if Christ’s birthplace gestures towards his self-abnegation, the time of his birth manifests his might. True, Christ “was born at a time of subjection” (ST III, Q 35, A 8, ob 1), during which the Roman Empire oppressed his native land, but God chose this time of servitude to proclaim a new and enduring “state of liberty” (ST III, Q 35, A 8, ad 1). This point, in fact, is accentuated by the very season of Christ’s birth. While winter is known for its short days and long nights, Christ was born just after the winter solstice, when daylight begins to lengthen again. As Thomas writes, “He came in order that man might come nearer to the Divine Light, according to Luke 1:79: To enlighten them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death” (ST III, Q 35, A 8, ad 3). De Incarnatione, then, is reflected even in nature, at least for those who have eyes to see (Matthew 13:16).

But herein lies the final enigma of Christmas—that its meaning can be elucidated but never demonstrated. Indeed, precisely as a philosopher, Thomas knew that any “philosophy of Christmas” must culminate in mystery. As the British Dominican philosopher Brian Davies (1951-) puts it, Thomas “does not pretend to be able to make sense of the Incarnation, if by ‘make sense’ one means comprehending what exactly the Incarnation involves.” Similarly, then, the attempt to reason through the significance of Christmas not only fails to render the Savior’s birth transparent to us, but it reinforces “our profound ignorance when it comes to what divinity is.” This conclusion does not abandon reason altogether, for Thomas presupposes that “the articles of faith can be defended against charges of contradiction” and that “we know enough to be able to say with respect to some things what naturally belongs to them, how they should be described, and what their abilities are in general.” So it is too with Thomas’ “philosophy of Christmas,” which takes the Incarnation as its starting point and terminates in a trio of paradoxes—that God has a mother; that God was born (temporally) in a small Palestinian town; and that God gave us the gift of salvation in a time of political oppression and earthly darkness. Kierkegaard, I daresay, would approve.

Merry Christmas to all Just FYI readers, both old and new!

Christ was born when daylight begins to lengthen again. Christ brings light. I have to be impressed by Aquinas’s insight.